Fat wraps around our body to keep us in warmth and comfort. Fat also wraps around nerve cells, especially those that have long processes connecting distant regions. The fat that clothes around our brain cells occur in the form of myelin; this is what gives the whiteness to the so-called white matter that is made of long conduits called axons. As we grow, this myelin cloth stretches up to cover more of the neuronal neck, thus encroaching on the grey matter that is made of nerve cell bodies. This slow encroachment peaks by the 3rd decade of life, coinciding with the typical age of onset of psychosis.

What purpose does myelin serve to the neurons? Myelin’s insulation provides nourishment (metabolic support), thus supplying the endurance needed for the rapid conduction of signals along the long axonal fibers. More recent discoveries show that within the grey matter, myelin sheaths also support smaller sized neurons with predominantly inhibitory function. Brain regions with a higher amount of myelin may be more ‘plastic’ or flexible to external influences.

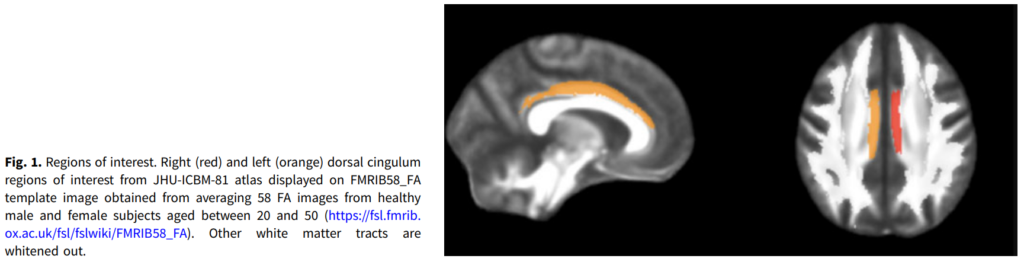

In some forms of severe psychosis, such as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder, the white matter appears less healthy at various places, likely due to lower myelin content. Patients with more severe functional deficits display more white matter aberrations. Using a sophisticated myelin measurement technique in ultra high-field (at a magnetic field of 7-Tesla strength in a scanner, which is 200 thousand times greater than earth’s surface magnetic field strength of 0.305 x 10-4 Tesla), we also noted that myelin reduction is prominent in fibers connecting visual processing regions to frontal cortex. The speed with which patients processed visual information was slower when this pattern of ‘dysmyelination’ was more pronounced. Some of the more bizarre symptoms of psychosis, such as the belief that someone else is controlling our feelings, action and thoughts (called Schneiderian delusions, after the German psychiatrist who highlighted their importance in 1938), related to reduced myelin content in certain key pathways of the brain.

There are many therapeutic agents that might ‘repair’ myelin defects. Some of these drugs are being studied to treat multiple sclerosis, an illness that predominantly affects myelin. Understanding the causes and consequences of myelin aberrations in schizophrenia will go a long way in making therapeutic progress in this direction. Some of our recent collaborative work with colleagues in Chengdu, China has shown that ‘grey matter’ myelin is increased in some brain regions (that contribute to our language use, among other functions) while decreased in prefrontal cortex in schizophrenia.

We are very interested in pursuing myelin pathology in a more detailed manner in psychosis. One of our CIHR funded study focuses on the role of myelin on the so-called negative symptoms of psychosis. In this context, we collaborate with Dr. Ali Khan at the Robarts Research to pursue certain types of short fibers (‘U fibers’) that have a distinct myelination profile. These U fibers are likely critical for communication within the local neighbourhoods of the cortex. We are also studying the effect cannabis has on myelin in another CIHR funded study, along with Dr. Phil Tibbo at Dalhousie University, Halifax.

Ultra high-field imaging offers nuanced means to study myelin; in Montreal, we are collaborating with Drs. Christine Tardif and David Rudko at the Neuro and Dr. Mallar Chakravarty at the Douglas to get more insights into this promising therapeutic lead in psychosis.