The manufacturing process within the mitochondria of our body cells uses the oxygen we breathe and the glucose we consume to produce packets of energy that we need. One by-product of this manufacturing process is a group of molecules called ‘free radicals’. Free radicals are double-edged swords: they have a key role in cell-to-cell signal transmission and immune function against pathogens, but when abundant, their oxidizing property can potentially damage our cells. Such a damaging reaction is prevented by the presence of an antioxidant defense system in our cells. A failure of this checking process can lead to oxidative stress. Oxidative stress is considered to be an important contributor to many systemic disorders such as diabetes, hypertension, etc.

Oxidative stress has been proposed to occur in some patients with psychosis, depression and bipolar disorder, and several observations suggest that this could be a key defect that may precede the onset of illness. In our brain, the primary antioxidant is a molecule called glutathione (GSH), which is present in star-shaped cells called astrocytes. There are two good reasons to focus on GSH when studying the oxidative stress status in mental illnesses: firstly, with neurochemical imaging techniques in a MRI scanner, we can measure the precise quantity of GSH in a given region of the brain; second, there are many well-tolerated health supplements that can be used to boost GSH levels in the brain. Together, this makes a perfect recipe to identify those who have low levels of GSH and give them interventions to improve it.

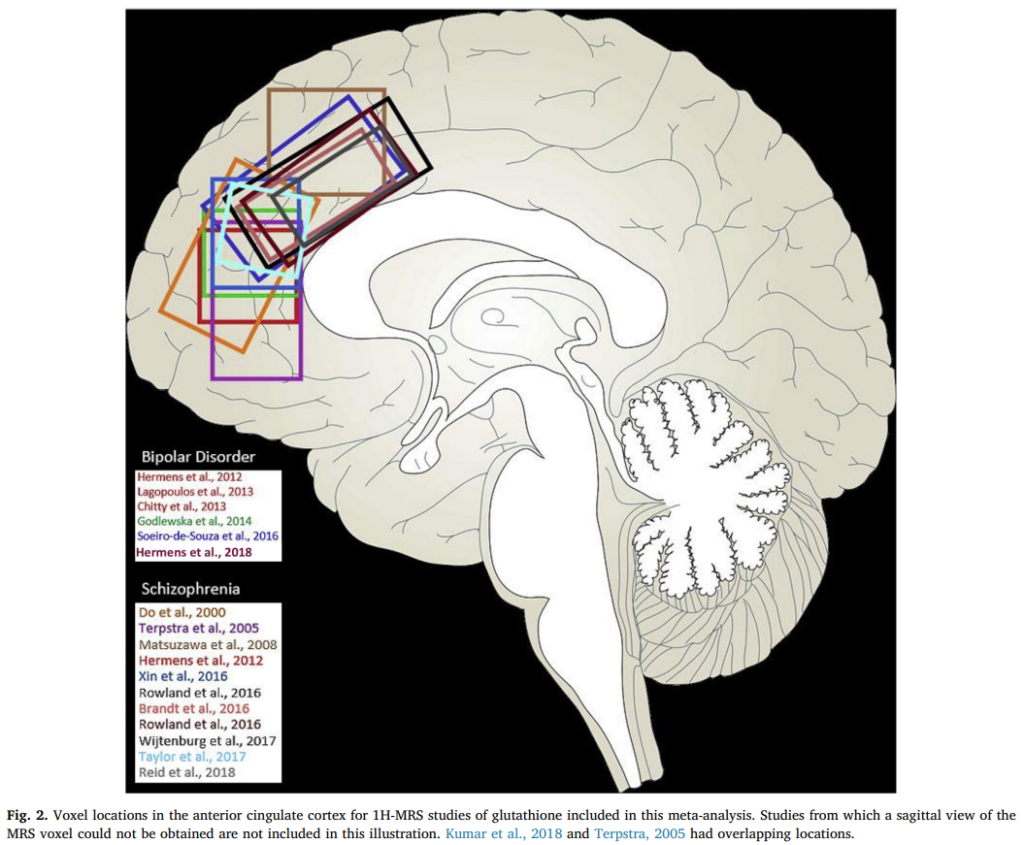

We have been closely looking at the levels of GSH in a region of the brain called the anterior cingulate cortex, from where reliable measurements can be made using a neurochemical imaging technique called Magnetic Resonance Spectroscopy (MRS) using a 7-Tesla MRI scanner. Our initial synthesis of several MRS studies at various strengths suggested a small but significant reduction of GSH in established cases of schizophrenia, while a small increase was notable among those who had bipolar disorder. Interestingly, in untreated prodromal stages and during first episode psychosis, GSH levels are indeed higher than expected in patients, especially in those who have better social and occupational functioning and employment/education status after a psychotic episode. Dr. Kara Dempster, during her graduate studies supported by a Canada Graduate Scholarship Award from the CIHR, demonstrated that the presence of higher GSH in ACC is also associated with a faster time to respond to antipsychotic treatment, once it is initiated. On the other hand, those who develop residual schizophrenia tend to have lower GSH levels in several brain regions (as shown by Dr. Jyothika Kumar, former graduate student).

Brain GSH levels change in a dynamic fashion in response to oxidative stress that may be prominent during early psychosis. Modelling cortical microcircuit in the ACC and another key region called insula (both part of the Salience Network), Dr. Roberto Limongi from our group has demonstrated that GSH levels may counteract glutamate-related effects on brain connectivity in untreated first episode psychosis. This is important because an excess of the excitatory signalling mediated via glutamate is considered to have a damaging effect on the brain (excitotoxicity).

In keeping with the observed individual differences in GSH levels among patients with psychosis, we are currently considering the possibility that there may be a subgroup of patients who are not able to modulate the GSH levels in an adaptive fashion, leading to treatment resistance and poorer functional outcomes. If true, early identification and treatment (possibly with antioxidants) of those at-risk of vicious oxidative stress (as proposed by Kim Do, Michel Cuenod and colleagues) may avoid poor functional outcomes later in this illness. Longitudinal clinical studies are needed to confirm this hypothesis.

We are very interested in pursuing the effects of antioxidant treatments on the functional outcomes of psychosis. Our access to MRS technology (in collaboration with Dr. Rob Bartha and Dr. Jean Theberge at Western University) as well as the potential to conduct longitudinal studies in patients with psychosis from a very early stage offers an immediate possibility of progress in this regard. So, watch this space!